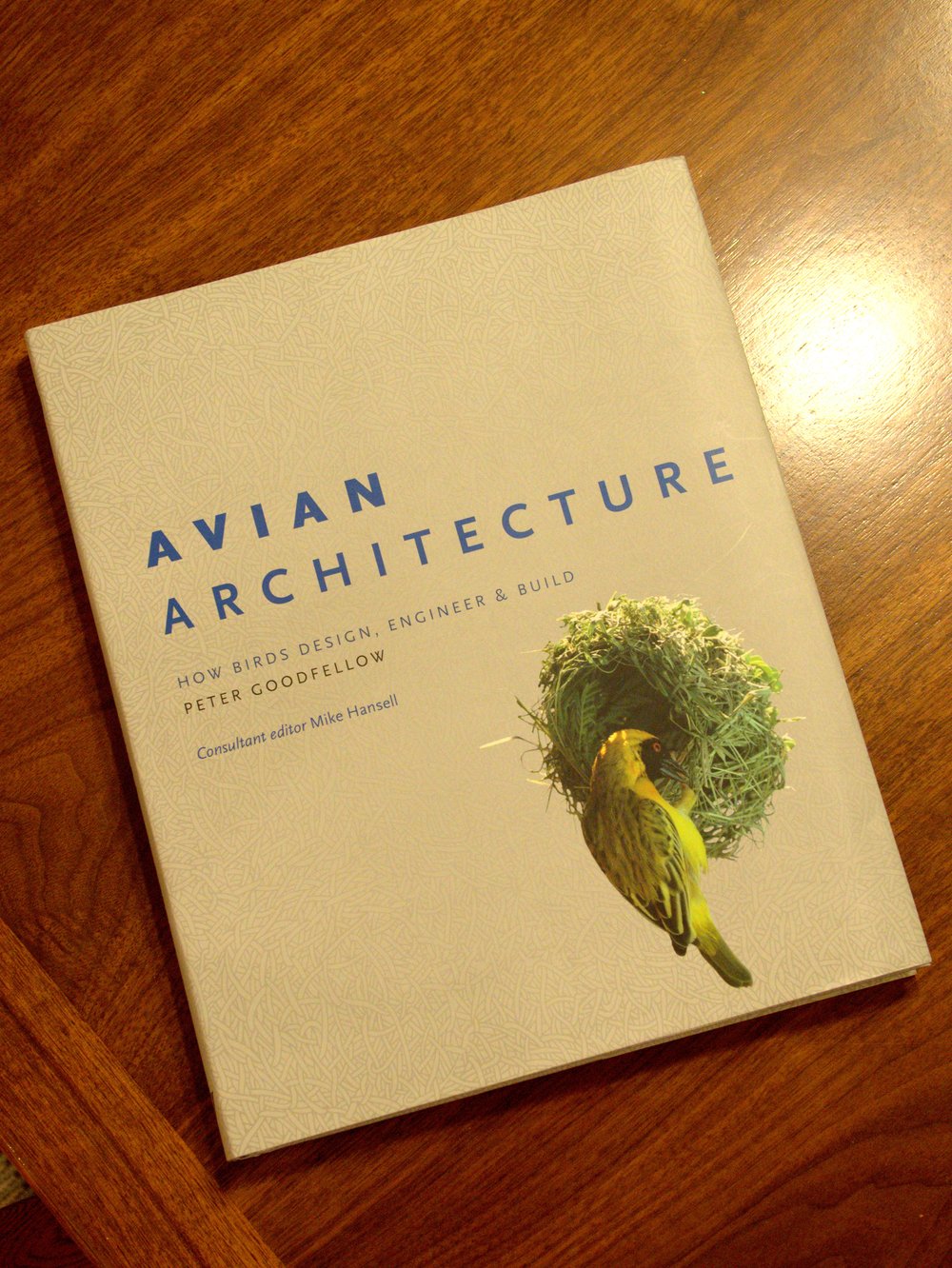

Master human architects skillfully design dwellings that optimally meet their clients’ needs and fit in well with their surroundings, both functionally and aesthetically. Equally so are the goals of birds as they construct their nests. Indeed, given the importance of the nest for successful reproduction and nurturing of the young, one wonders why other mammals have not cultivated this ability, through natural selection, to as high a degree as birds. Peter Goodfellow in Avian Architecture ponders these questions and further delves into the entire realm of avian engineering, from overall design plans to intricate construction techniques.

Master human architects skillfully design dwellings that optimally meet their clients’ needs and fit in well with their surroundings, both functionally and aesthetically. Equally so are the goals of birds as they construct their nests. Indeed, given the importance of the nest for successful reproduction and nurturing of the young, one wonders why other mammals have not cultivated this ability, through natural selection, to as high a degree as birds. Peter Goodfellow in Avian Architecture ponders these questions and further delves into the entire realm of avian engineering, from overall design plans to intricate construction techniques.

The book is well organized. Each chapter begins with an overview of a specific type of nest with key structural characteristics and building methods, and prominent representative families. Next, the architectural characteristics of each nest type are delineated as ‘blueprint drawings,’ crisp blue and gray drawings highlighting the component materials and their interrelationships in design, shape, structural support and strength. With photographs, in the ‘materials and features’ section, Goodfellow continues on to discuss unique aspects such as camouflage, distinctive adaptations to habitat and incorporation of available material. The 'building techniques’ pages expound upon remarkable skills such as the stitching and weaving of some passerines. ‘Case studies’ conclude each section; he discusses an individual species’ nest type in depth, including notes on courtship and mating, monitoring of eggs and care of young.

The author outlines eleven nest categories: scrape nests; holes and tunnels; platform nests; aquatic nests; cup-shaped nests; domed nests; mud nests; hanging, woven and stitched nests; mound nests; colonies and group nests; and courts and bowers. To the uninitiated, this may seem detailed, but Goodfellow’s presentation of each type is so lucidly well-composed, explained and diagramed that the read feels assured of a comprehensive understanding of each discrete nest type. Also, the author brings in examples of birds from around the globe, greatly expanding beyond the nest types we commonly encounter.

I will mention a few I found especially fascinating. The female Great Hornbill (a huge bird of India and the Far East) nests in the cavity of a dead tree and, once settled in, the female seals up the opening with mud to a narrow slip and there remains for months, completely dependent on the male for food. The Magpie Goose, a waterfowl, builds a reed platform nest by clutching reeds in her beak and folding them down about her, forming a base like the spokes of a wheel.

Red-eyed Vireo nestAs you continue through the book, you quickly discover that nests are not mere piles of debris, sticks, grasses, etc. Rather, just as most of us have learned that baskets are made by twining and binding strands around upright spokes, likewise birds carefully integrate weaving material about vertical supports. Aquatic nest builders depend upon standing reeds, rushes and sedges for structural bracing. Cup-shaped nest-builders often use the triple fork of a branch as a foundation. Woven nests (ex. Oriole) do not by happenstance have a plaited surface appearance. Rather, Goodfellow illustrates the intricate weaving methods, as the bird, with her beak, pushes a grass strip through, tucks in the short end, threads the long and through nearby fibers, pulls it out and around and makes loops, through which it pulls strands to create a secure binding. A Baltimore oriole nest comprises 20,000 such shuttle movements and takes four and one-half days to build.

Red-eyed Vireo nestAs you continue through the book, you quickly discover that nests are not mere piles of debris, sticks, grasses, etc. Rather, just as most of us have learned that baskets are made by twining and binding strands around upright spokes, likewise birds carefully integrate weaving material about vertical supports. Aquatic nest builders depend upon standing reeds, rushes and sedges for structural bracing. Cup-shaped nest-builders often use the triple fork of a branch as a foundation. Woven nests (ex. Oriole) do not by happenstance have a plaited surface appearance. Rather, Goodfellow illustrates the intricate weaving methods, as the bird, with her beak, pushes a grass strip through, tucks in the short end, threads the long and through nearby fibers, pulls it out and around and makes loops, through which it pulls strands to create a secure binding. A Baltimore oriole nest comprises 20,000 such shuttle movements and takes four and one-half days to build.

Most of us are familiar with nests of twigs, grass, reeds, lichen, moss, and mud. Some mound builders, such as the Adele Penguin, use stones. Horned Coots (South America) pile up stones offshore to build a safe artificial island nest.

Some species build nests in groups or colonies. The tightly packed nests of swift colonies are a familiar example. But the Sociable Weaver constructs one large nest with multiple inlets like a gigantic apartment block.

The Bowerbird’s engineering efforts aim at ‘statement architecture designed solely to attract females.’ The construction activity itself is a type of courtship behavior. The attracted female, after mating, flies off to build a commonplace nest. The three types of bowers, stage, avenue and maypole, attest to their display purposes, and in the case of the Satin Bowerbird, go to the extreme of decorating the entryway with distinctly blue feathers and stones.

Although nest building has long been considered innate and instinctive, learning may also play a role. The Vogelkop Bowerbird male spends four to seven years practicing bower making before he breeds.

This is an engrossing book. The numerous types of bird nests are explicitly described by the succinct ‘blueprint’ illustrations, followed by step-by-step diagrams of construction techniques, case examples with photos, and further discussion of nest habitat and mating and incubation behavior.

I purchased the book from E. R. Hamilton, Bookseller Co., PO Box 15, Falls Village, Ct 06031-0015, on sale for $9.95. You could also try Amazon, or better yet, a local store like Bookmobile or Phoenix Books (for special order).

Click here is a list of other RCAS book reviews: