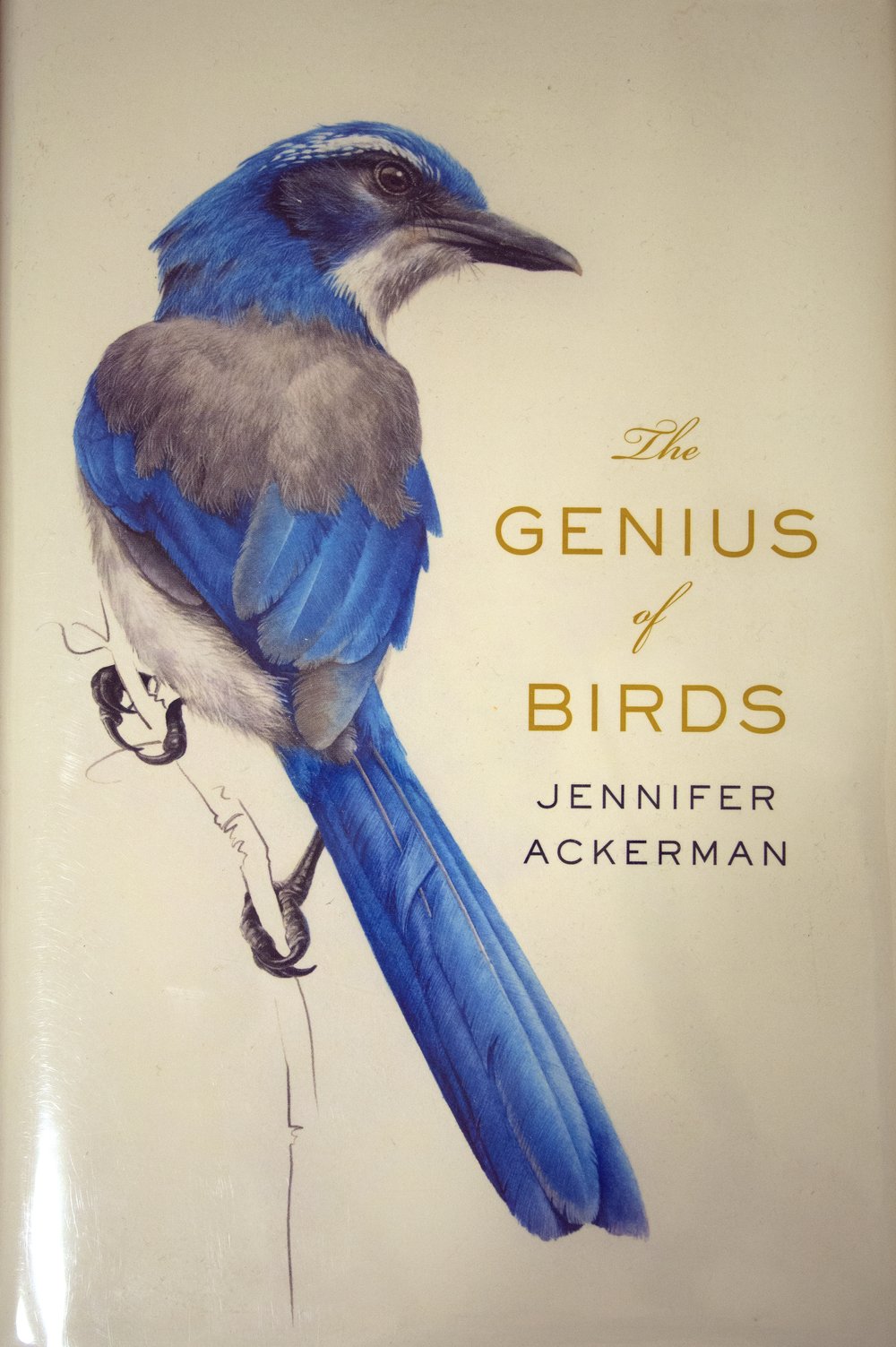

In her engrossing book, The Genius of Birds, Jennifer Ackerman, elucidates recent findings that are shifting our understanding of bird intelligence. Indeed, birds have borne the brunt of our disrespect, from the ‘bird-brained’ stupid, foolish person, to the ‘lame duck’ ineffectual politician. The concept of ‘bird-brain’ arose from the belief that avian species possessed only diminutive brains since they functioned mainly by instinct. But, not only have scientists found that some birds have brains relatively large for their size, size matters less than where neurons are located, how they communicate at their synapses and how interaction with the environment drives neural activity.

In her engrossing book, The Genius of Birds, Jennifer Ackerman, elucidates recent findings that are shifting our understanding of bird intelligence. Indeed, birds have borne the brunt of our disrespect, from the ‘bird-brained’ stupid, foolish person, to the ‘lame duck’ ineffectual politician. The concept of ‘bird-brain’ arose from the belief that avian species possessed only diminutive brains since they functioned mainly by instinct. But, not only have scientists found that some birds have brains relatively large for their size, size matters less than where neurons are located, how they communicate at their synapses and how interaction with the environment drives neural activity.

Avoiding the word ‘intelligence’ because of its anthropomorphizing human connotations, animal scientists now prefer the term ‘cognition,’ defined as any mechanism by which the animal acquires, processes, stores and uses information. It usually refers to mechanisms involved in learning, memory, perception and decision making. Higher forms of cognition constitute insight, reasoning and planning; however, forms are attention and motivation.

Cognitively defining intelligence, however, opens up another problem – how to measure it. There is no standard IQ test for birds, so scientists devise puzzles for birds, in order to reveal their problem-solving abilities. Such meticulously designed laboratory experiments have been very useful in disclosing bird skills, such as that of ‘007,’ a New Caledonian crow, that was able to shape one tool and use it to obtain another too, which was ultimately employed to extract a food reward (‘mega-tool use’).

But Ackerman cautions that judging bird intelligence by speed and success at solving lab problems, may overlook many variables, such as the boldness or fear of an individual. Birds that are faster at solving tasks may not be smarter, just less hesitant to engage in a new task.

Thus, to avoid the artificial framework of the lab experiment, another approach would be observation, of birds doing routine as well as unusual or new behavior in their own habitat. Though lacking the rigors of an experiment’s strict parameters, anecdotes, from both professionals and amateurs, have resulted in an enormous amount of useful enlightening data. These have been validated as repeated observations have confirmed them. For example: Green-backed herons have been found to use insects as bait, placing them lightly on the surface of water to lure fish.

So in amassing all the research to date, wherein does our understanding of bird intelligence lie? What birds are the smartest and why? Scientists have concluded that it is the ‘primary innovators,’ mainly crows and parrots; then grackles, raptors, woodpeckers, hornbills, gulls, kingfishers, roadrunners and herons. Innovation is accepted as a measure of cognition. Another example is owls scattering clumps of animal feces near the opening of their nest chambers and watching for unsuspecting dung beetles to scuttle toward their trap. Or consider the woodpecker finches of the Galapagos when they use their skills to chip away at bark, producing wood splinters to probe crevices beyond the reach of their beaks.

Delving deeper, Ackerman questions whether they are evolutionary forces driving bird innovation. Two theories postulate the source of such forces. First, there are the ecological problems birds encounter, especially foraging (how to find enough food, how to fetch hard to get foods, remembering where seeds are hidden). Secondly, there are social pressures – getting along with others, thieves, finding a mate and carrying for young. From this has arisen the ‘social intelligence hypothesis,’ the idea that that a demanding social life might drive the evolution of brain power.

Having covered the larger, overarching theories, Ackerman then investigates lesser, more discrete topics and issues.

Brains of many birds are actually considerably larger than expected for their body size. Reproductive strategy may play a role. Species that are precocial (born with eyes open and able to leave the nest in a day or two) have larger brains at birth than altricial birds (born naked, blind and helpless and remain in the nest until they are as big as their parents). On the other hand, birds that migrate have smaller brains than their sedentary relatives. Since brains consume a lot of energy, this would seem reasonable.

Calls, songs, mimicry and the virtuosity they entail, are address in a lengthy chapter. These vocal feats are brought about by the ‘syrinx,’ somewhat analogous to our vocal cords, but more complex in its anatomy and innervation, enabling the simultaneous production of two harmonically unrelated notes at the same time. Nonetheless, such structurally well-equipped birds must still learn by trial and error, working through wrong, off-key notes, to produce their vocalizations.

Nest building requires many intellectual abilities besides instinct: learning, memory, experience, decision making, coordination and collaborations.

And of course, there is the everlasting mystery of migration. Some new theories have arisen. ‘Infrasounds’ are produced by many natural sources, but mainly oceans. Interacting waves in the deep ocean and movements of sea surface water create a background noise in the atmosphere that can be detected with low frequency microphones. Birds may be capable of detecting such low frequencies and use them as a guide through the ‘soundscapes.’ Or the ‘olfactory navigation hypothesis’: pigeons with several olfactory nerves never returned home! Homing pigeons have very large olfactory bulbs compared with non-homing domestic pigeons.

Much more awaits the reader of this engaging, in-depth book. Ackerman has done extensive research, attested by 50 pages of explanatory notes at the end. Yet, at 271 pages, she has consolidated the heavy science to a layperson’s comprehension. My one criticism would be the need for explanatory diagrams. Lovely pen and ink drawings introduce each chapter, but, for example, her description of the complex steps of the New Caledonian crow in constructing a hook tool from the leaves of the pandanus tree left me befuddled.

The book is available at the Rutland Free Library.